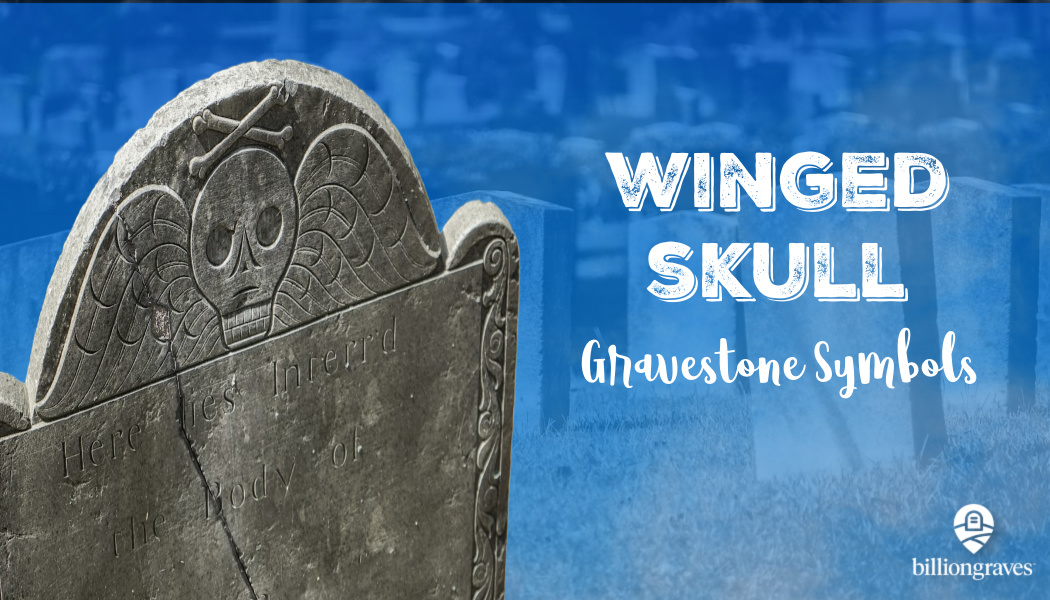

Winged skull gravestone symbols were common in 18th-century cemeteries. While they may look strange to us today – even morbid or creepy – they held important meaning for our ancestors.

Death was a frequent visitor to households in the 1700s. In many areas, it was a world of poverty with poor sanitation, malnourishment, and scant medical knowledge. Infant and child mortality were high. Epidemics of smallpox, measles, and whooping cough swept through communities, overcoming the most vulnerable.

Since death was an everyday part of this generation’s life, it makes sense that emblems of mortality made their way onto tombstones.

When gravestones first began to be engraved, many of the common people were illiterate. Not only could they not read or write, but the stonemasons who carved the gravestones couldn’t either. As a result, the engraved carvings were not meant as mere decorations but were symbols that the layman could understand.

What did winged skull gravestone symbols mean and how did they evolve? Let’s start with the forerunners of this symbol . . . the skull and cross bones.

Winged Skull Gravestone Symbol Forerunners

Before the winged skull gravestone symbols, there were simply skulls and crossbones.

Some of the earliest gravestones, especially those in England, Scotland, Ireland, and Colonial New England, had skulls and crossbones on them.

Why? Did they mark a pirate’s final resting place? Probably not. A gravesite of someone who was poisoned – similar to the crossbones warning on poisonous substances today? Nope.

These were a reminder to all who passed by the graveyard that death was inevitable and life was short . . . SO YOU BETTER BE GOOD!

Burial sites during the 18th century were usually in churchyards. So church-goers would see these macabre symbols coming and going from services. The symbols served as a means to keep one thinking with an eternal perspective.

Click HERE to see the skull and cross bones gravestone at the final resting place of Sarah Revere, wife of Paul Revere (American Revolutionary patriot who rode through the streets with a warning, “The British are coming!”) on the BillionGraves website.

The Skull & The Hourglass

The life expectancy in England’s 1700s was only about 35 years, in large part due to high infant and child mortality rates.

Those who lived in the early colony of Virginia in seventeenth-century New England could expect to live less than 25 years, with about 40 percent dying before reaching adulthood.

With such short life spans, it made sense for gravestones to have hourglasses on them to indicate the quick passage of time.

“Remember me as you pass by,

As you are now so once was I,

As I am now you soon must be,

Prepare for death and follow me.”

Together, these gravestone symbols say, “Life is fleeting, death is inevitable, use every single moment wisely!”

“My glass is run, and yours is running,

Mind death for the judgment’s coming.”

For Whom the Bell Tolls

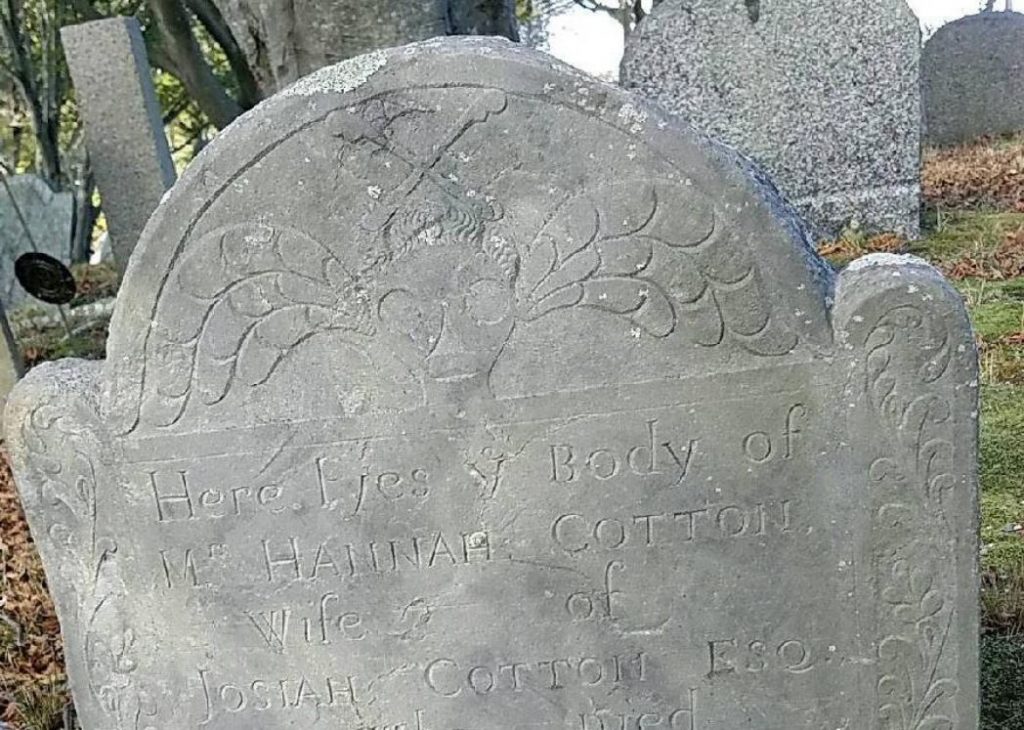

This gravestone above from Scotland has six symbols on it. Starting at the top, there are some leaves beneath an arch. The leaves are symbolic of life. The arch represents heaven’s gates. So read together, the symbol means the living soul who has died is passing through heaven’s gates.

Next, there are four more symbols loosely arranged in a circle. At the top of the circle, is an hourglass. The sand passes through the hourglass, just as this person quickly passed through mortality.

To the right, are crossbones which are, of course, a reminder of death. These crossbones are particularly interesting because they are somewhat anatomically correct femur bones, complete with the ball to fit into the hip socket.

The third symbol, at the bottom of the circle, is a bit worn and hard to see but it is a bell. The bell is representative of a church bell that rings to call people to the funeral.

And the final symbol in the circle is a skull, another reminder of death.

The hourglass, crossbones, bell, and skull are frequently seen together on 18th-century gravestones.

The final carving is across the bottom of the gravestone and it represents the deceased’s occupation as a farmer using a plow.

This Scottish gravestone includes the same four gravestone symbols of the skull, bones, hourglass, and bell.

When someone prominent died in the 18th-century, a funeral was held at the local church. To announce the event, a bell on top of the church was rung slowly and repeatedly until all had time to gather together.

Sometimes families would send a child or servant to run ahead to the church to see who had died. English poet and cleric, John Donne (1572-1631), wrote the line ‘for whom the bell tolls’ in a sermon to make a point that we are all interconnected and no man is an island unto himself.

Donne wrote, ” . . . any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.”

Winged Skull Gravestone Symbols

Over time, the skull and crossbones gave way to winged skull gravestone symbols. The wings were symbolic of a soul fleeing mortality. It added a message of hope and resurrection.

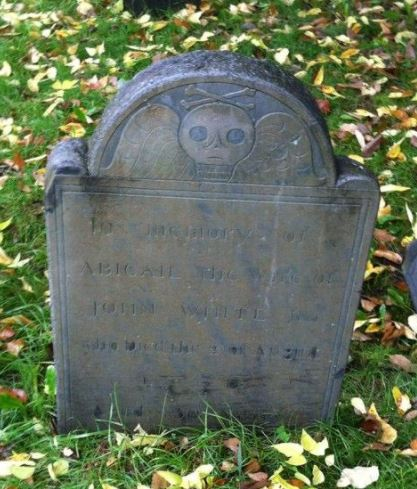

The gravestone above, from a graveyard in Salem, Massachusetts, combines the skull and cross bones with a pair of feather-like wings. (Abigail White, d. 1776, The Burying Point, Salem, Massachusetts)

This Boston, Massachusetts monument has not only a winged skull gravestone symbol but a winged hourglass. Time flies!

It is the final resting place of Elizabeth Pain, who was flogged twenty times for having a child out of wedlock. It is believed that she may have been the inspiration for the character of Hester Prynne in the novel The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne. (Elizabeth Pain, King’s Chapel Burying Ground, Boston, MA, Photo Source)

Many early gravestones had the Latin inscription “Memento Mori” on them which meant “Remember, you must die”. This was a grim reminder of life’s fragility to encourage people to live well.

The image above has double-winged skulls. And the epitaph cuts to the chase by simply saying, “Remember to die.” (Lydia Barton, The Burying Point, Salem, Massachusetts)

The tombstone above has the winged skull gravestone symbol at the top and the epitaph “Hodie Mihi Cras Tibi” beneath which is Latin for “Today me. Tomorrow you.” (Christian Hunter More, d. 1676, The Burying Point, Salem, Massachusetts)

The stark skull and hourglass are being softened on this gravestone with round posies and swirling leaves in the side panels and feather-like wings above the heart. (Hannah Bartlett, d. 1710, age 72; Burial Hill Cemetery, Plymouth, Massachusetts)

The Granary Burying Ground in Boston, Massachusetts is full of gravestones with winged skulls. Click HERE to check out a winged-skull gravestone on the grave of the 4-month-old baby sister of American Revolutionary patriot, Samuel Adams. Click HERE to see a pair of winged skulls for a husband and wife. And click HERE to see one for a 90-year-old woman who died in 1680.

Winged skull gravestone symbols are found in England too, like this one above from Bamburgh, Northumberland (Photo Source). It also has a set of scales to remind cemetery visitors of the balance between justice and mercy on judgment day.

Winged Skulls with Teeth

Some winged skull gravestone symbols had very prominent teeth like this one for Lottrop Bartlett, son of Samuel and Elizabeth Bartlett at Burial Hill Cemetery in Plymouth, Plymouth, Massachusetts.

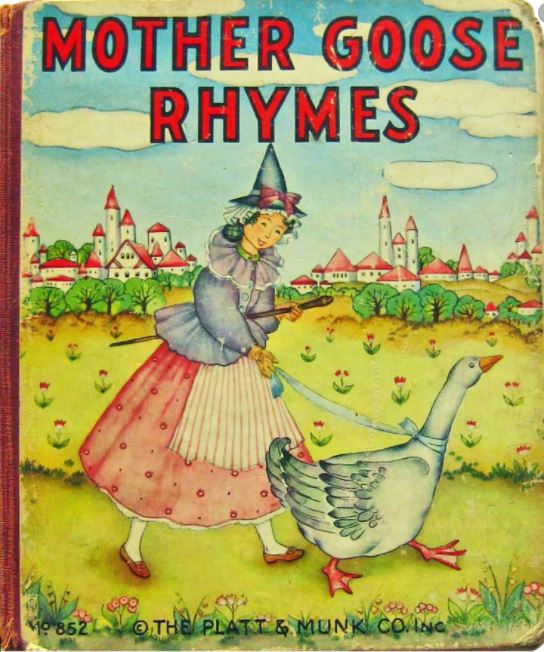

This winged skull gravestone symbol with prominent teeth is on the grave of Mary Goose, wife of Isaac Goose of Boston, Massachusetts. The headstone became a tourist attraction when the rumor spread that Mary Goose was also known as “Mother Goose” who was famous for her rhymes and tales such as “Hickory, Dickory Dock; Hey Diddle, Diddle; and “Jack and Jill“.

Others say that the real Mother Goose may have been Isaac’s second wife, Elizabeth. She had six children to add to Isaac’s ten and loved entertaining them with her little stories and tunes.

When Elizabeth’s grandchild was born to her daughter and son-in-law, Thomas Fleet, Elizabeth was delighted. A Boston tourism website says that “Like all good grandmothers, she was in ecstasies at the event. She spent her whole time in the nursery, and wandering the house, pouring forth, in not the most melodious strains, the songs and ditties which she had learned in her younger days, greatly to the annoyance of the entire neighborhood and to Fleet in particular, who was a man fond of quiet.”

Thomas Fleet eventually gave up on trying to quiet his mother-in-law, wrote down her rhymes, and published them in a book.

Skulls with Heart Noses and Mouths

Prominent teeth continued to be a common feature on winged skull gravestone symbols as well as on skulls with crossbones. To this was added heart-shaped noses.

Then the heart-shaped noses crept downward, flipped upside down, and became heart-shaped mouths.

The heart-shaped mouth on a winged skull gravestone was symbolic of the soul leaving the body. (Peter Riply, died 1742, Hingham Center Cemetery, Massachusetts)

Winged Skull Gravestone Symbols with Hair

Nice hair-do. (Okay, was that you laughing? I heard that!)

By the end of the 1700s, the winged skull gravestone symbols had sprouted hair. At least for the young people it did – children and younger adults. The gravestone above marks the final resting place of a sea captain, Cyrus Palmer, of Richmond, Virginia who died at the age of 26. Notice how his “wings” are also his collar.

His epitaph says,

“Death is uncertain,

Yet more sure,

Sin is the wound,

Christ is the cure.”

This winged skull gravestone symbol is hardly recognizable as a skull anymore. It has hair with crossbones on top and wings that seem to come out of the ears.

Winged Faces & Cherubs

Gradually, faces were fleshed out. This one has an oval-shaped face and curly hair. It is the gravestone of Deborah Seabury (widow of Samuel) at Myles Standish Burial Grounds in Duxbury, Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Rounded faces often signified children or youth. This gravestone is for George Partridge, age 18, buried at Myles Standish Burial Grounds, Duxbury, Plymouth, Massachusetts

George Cooper, who died in 1795 at age 2, has a marker (at Burial Hill Cemetery in Plymouth Massachusetts) that has definitely evolved from the winged skull gravestone symbol to a little face with wings.

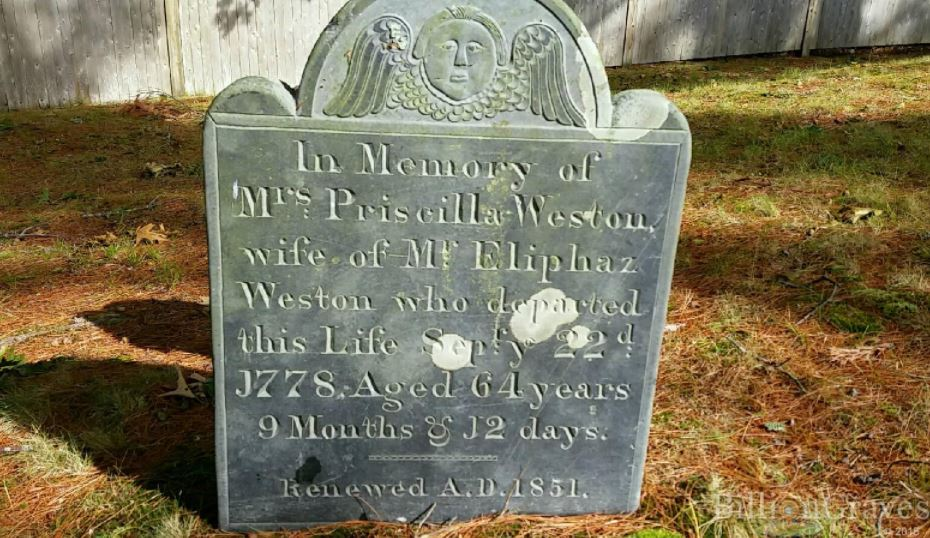

This rounded face with a bird-like torso and wings marks the grave of widow Priscilla Weston at Myles Standish Burial Grounds in Duxbury, Plymouth, Massachusetts.

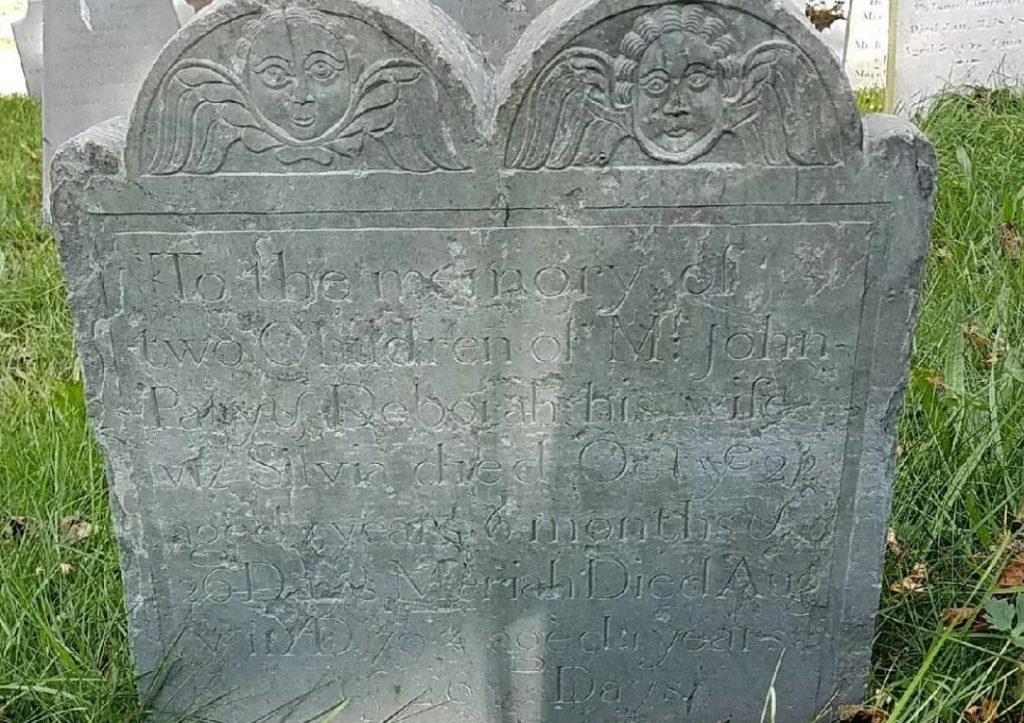

Double headstones with winged faces are somewhat rare. This one marks the grave of sisters that passed away in August and October of 1793 at the ages of 1 year and 6 months.

By the end of the 18th-century, the winged skull gravestone symbols had transitioned to look like little angels.

Taking Gravestone Photos with the BillionGraves App

Taking photos of gravestones with the BillionGraves app will help preserve precious history. Each photo you take is automatically tagged with the GPS location, allowing the gravestones to be plotted on a map. Then the information is transcribed and made available for families around the world who are searching for their ancestors.

If you would like to volunteer to take gravestone photos with your smartphone click HERE to get started.

You are welcome to do this at your own convenience, no permission from us is needed. If you still have questions after you have clicked on the link to get started, you can email us at Volunteer@BillionGraves.com. We’ll be happy to help you!

Groups of 20 or more may email us at Volunteer@BillionGraves.com for additional resources and ideas.

To learn more about cemetery symbols check out these BillionGraves blog posts:

- Understanding Cemetery Symbols Part I

- Understanding Cemetery Symbols Part II

- Understanding Cemetery Crosses

- Irish Gravestone Symbols

- Egyptian Gravestone Symbols

- Fraternity Gravestone Symbols

- Catholic Gravestone Symbols

Happy Cemetery Hopping!

Cathy Wallace