Gone but not forgotten. Not forgotten because WE are remembering the Irish Famine.

Each St. Patrick’s Day my heart is turned to the Irish. My own father was born on St. Patrick’s Day and was fittingly given the middle name of Patrick.

We live in America now, because our Irish ancestors made the difficult decision to survive the Great Famine of 1845-1849 by emigrating. There simply wasn’t enough food for all the mouths, so our ancestors scattered – not only to America but to Canada and Australia. This allowed for a few to stay in Ireland.

How they must have longed for one another over the years. The ocean that parted them prevented visits. And illiteracy – due to a lack of available education in Ireland – prevented them from even writing letters.

Over the generations, descendants forgot the names of their great-grandparents and even the names of their ancestral villages.

But this past month, my brother and I have found more than 40 Irish relatives thanks to documented gravestones, DNA, the patience guidance of a kind missionary at the FamilySearch Library in Salt Lake City, Utah, and many hours of research.

Wherever you live all over the world, you can help others find their ancestors by documenting a cemetery near you with the BillionGraves app or by transcribing gravestone data on the BillionGraves website.

Life Before the Irish Famine

The pre-famine maps we found for our family’s homeland in County Limerick show that there was a large estate with a manor house near the River Shannon. It sat idle most of the year, waiting for an English Lord who would visit once or twice a year.

Surrounding this estate were small stone cottages with thatched roofs where the Irish tenants lived. The homes were sometimes whitewashed creating a pretty picture against the green rolling hills for a season, but belying the misery inside.

There were often more than a dozen family members sharing a small cottage with their farm animals. The floors were of beaten earth and dried sheepskins were hung over the windows to cut down on the drafts that blew right through the house.

Our ancestor’s land records showed that they rented a house (everyone rented from the English) with a garden, an office (AKA a barn), a cow shed, a piggery, and a bog.

At first, I was confused as to why the Irish would bother to record bogland in an official record. To me, it seemed a useless swamp. But to my Irish ancestors, it was a valuable source of fuel.

They used a wooden spade to slice off “bricks” of mud which they then laid out to dry in the sun to be used later for cooking and heating.

And what did they cook? Potatoes, of course! Sometimes a few turnips, cabbage, or buttermilk graced their tables. Meat was a rarity, eaten occasionally on Easter or Christmas. But mostly it was potatoes.

A single acre of potatoes could yield up to 8 tons of food, enough to feed a family of 6 for a year, with scraps for their animals.

Potatoes were boiled and eaten whole with the skins on. Or they were baked in a fire. When stuffed in a pocket, baked potatoes kept their fingers warm from morning until they were eaten at the noon meal.

Sometimes boiled potatoes were broken into pieces, mixed with a little butter or milk, and then set in the embers with red coals on top to roast.

Even generations later, every time our family cooked potatoes, my father quoted his grandmother, saying, “You can’t kill a good potato.” This meant that if it wasn’t rotten, it doesn’t matter how you cook it.

Rotten Potatoes

Oh, but what if it was rotten?

In August of 1845, after three weeks of rain and fog, Irish farmers watched in horror as the stalks and leaves of their potato plants began to turn black. The stench coming from these blackened, drooping plants was wretched.

Families rushed to get the potatoes out of the ground to save what little was left around the blighted rot at the center of each one. They trimmed the pieces that were usable from around the edges, wondering how they would survive the winter and what they would use as spuds to start the next year’s crop.

The Starving Years

Children were sent into the fields to search the mounds of dirt for any potatoes that may have been overlooked. They sometimes returned with only wild mushrooms or nettles for a thin soup.

During the famine, many Irish folks ate half-cooked potatoes — when they could get potatoes at all. Half-cooked potatoes took longer to digest so they seemed more filling and they were called “potatoes with the bone in them.”

What was a mother to do when her milk had dried up and her baby was dying? She may get desperate enough to kill their last chicken to make a little broth. It may help for a few days.

By 1846, farmers planted what they could in the spring but once again at harvest time the potato crop was struck with blight.

The English provided work for Irish men, digging ditches or building roads. But many were already too weak for such heavy labor and died trying to provide for their families.

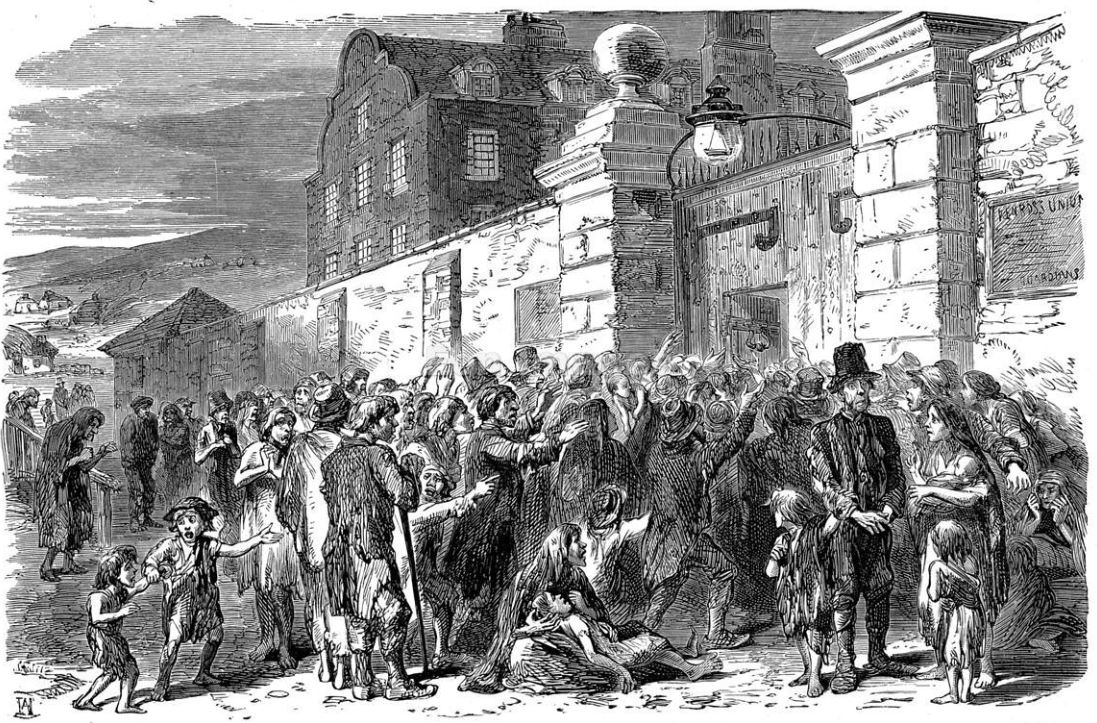

When the man of the house died, the women and children often went to the workhouses or poorhouses that had been set up by the English rather than face starvation.

The Irish Famine Workhouse

Life inside an Irish workhouse was purposefully brutal in order to discourage all but the truly desperate from entering.

Sometimes entire families entered the workhouse together. Males and females were separated, only to see each other during Sunday worship services, if at all.

Those who arrived at a poorhouse were usually at death’s door due to starvation, dysentery, and fever. The overcrowded conditions didn’t help the situation and disease ran rampant.

Inmates – as poorhouse residents were called – were set to work breaking stones or crushing bones to produce fertilizer.

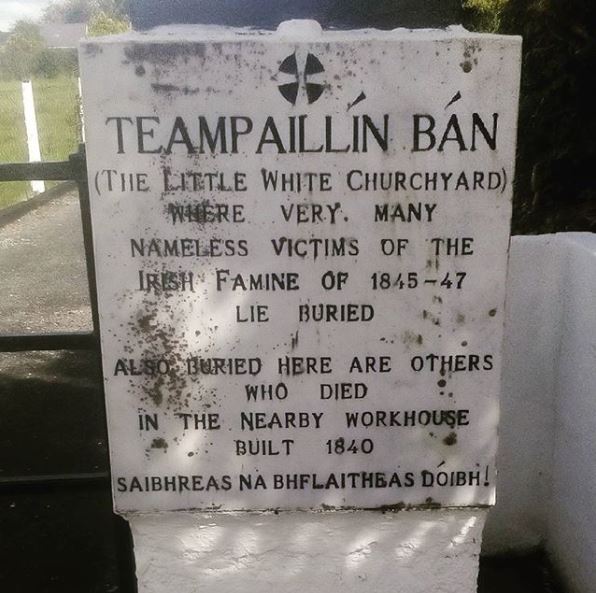

Those who died at the workhouse were sometimes buried in a mass grave.

Others were put in a wooden coffin and rolled out to the burial ground on a cart. After the coffin was placed in the ground, a false bottom dropped and the body fell through to the earth. The wooden coffin could then be lifted out and reused.

Surviving the Irish Famine

The English sent some Indian corn or maize to those still striving to survive outside the workhouses, but it was poorly ground and caused abdominal pain and diarrhea.

In 1847, Britain passed the Extended Poor Law, a tax that shifted the cost of the maintenance for poorhouses and the feeding of the starving masses from the British government to the Irish landowners.

The effect was that many English landowners decided to evict their Irish tenant farmers. Between 1847 and 1851, the eviction rate rose by nearly 1000%.

To further encourage the tenant farmers to leave, their homes were sometimes knocked down as the families stood by and watched.

Some English landowners allowed their Irish tenants to live on the land rent-free, but this caused them to eventually go broke.

Others provided their Irish tenants with free passage on ships bound for America, Australia, or Canada. This freed up the land for English cattle to graze.

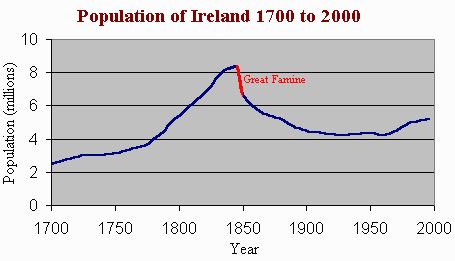

Prior to the Irish potato famine, the population peaked at about 8.2 million. A decade later, the population had dropped to about 6.5 million. Death and emigration accounted for the decline in nearly equal proportions.

Today there are nearly 5 million people in Ireland, while there are an estimated 55 million people worldwide who can trace their ancestry back to the Emerald Isle.

Irish Funeral Customs

During the British occupation of Ireland, funerals became a social event because it was one of the few times they were allowed to gather in groups.

In better days, the Irish held “a wake” when one of their loved ones died. Unlike traditional funerals, a wake was not a sad affair. Rather, it was a time of storytelling, merry-making, game-playing, and pranks.

Family and friends met at the home of the deceased, bringing along enough stout (a black beer) to last for several days. The deceased was sometimes even propped up in a corner to watch the festivities.

It was common for contests of strength to be held including lifting the corpse. A typical prank was to have someone hide beneath the bed on which the corpse was laid out and then shake it when a visitor walked in to scare them out of their wits.

Some say that the tradition of the wake originated with Celtic pagan rituals, where the living watched over the body of the dead for three days.

Others say it is a nod to the ancient Jewish practice of leaving a burial chamber unlocked for three days so family and friends could return to check for any signs of life in case a terrible mistake had been made.

Another myth holds that the Irish who drank stout from pewter cups were sometimes the victims of lead poisoning which put them into a catatonic state that resembled death. Then in the middle of their own wake, they would wake up!

Irish Famine Victims Remembered

But during the Irish famine, the deceased were often piled into mass graves by the thousands, without ceremony, prayers, or good-byes.

But today, in many places across Ireland mass gravesites have now been marked with a single stone in memory of those who suffered and died during the Great Famine.

There are now more than 100 memorials to the Irish Famine worldwide.

One of the most striking memorials is a set of bronze sculptures in Dublin created by Rowan Gillespie to memorialize the Irish Famine emigrants. It features skeletal-like men, women, and children dressed in rags boarding a “coffin ship”.

Finding Irish Ancestors

Finding Irish ancestors – especially when they were scattered across the world due to the Irish Famine – can be as tricky as a leprechaun!

Here are a few tips:

- Start by interviewing your living relatives – ask if anyone has old photos, stories, or legends to share

- Take a DNA test

- Connect with your DNA matches (these are often descendants of your common ancestor on another line) and interview them as well

Resources for Irish Research

- Ireland XO

- Griffith’s Valuation

- 1901 and 1911 Census Records

- Catholic Parish Records

- Irish Townland Database

- Ship Immigrant Passenger Lists

- JohnGrenham.com

- Search by surname

- Search by places to see the which years particular baptism and marriage records are available for each Parish

- After a limited number of searches, the site will request membership fees

Irish Gravestone Symbols

If you know how to read the symbols on Irish gravestones, you can learn more about the people who put them in the cemeteries – both those who survived the Irish Famine and those who did not.

Click HERE to read a BillionGraves blog post titled Irish Gravestone Symbols.

This Irish Celtic Cross is a nod to ancient pagan sun-worshipers as well as a Christian symbol. This gravestone combines the Latin Cross in the forefront with a circle, representing the sun, at the back. Irish legends claim that St. Patrick introduced the Celtic cross in Ireland as a way to guide pagans to Christ.

IHS are the first three initials (iota-eta-sigma) of the name Jesus in Greek: ΙΗΣΟΥΣ. This symbol was introduced in Ireland in about 1780 and was highly popular around 1810 to 1830.

Taking Gravestone Photos

Whether you have Irish ancestors or not, you can bless the lives of others by taking photographs with the BillionGraves app at a cemetery near your own home or as you travel. Each photo is automatically linked with a GPS location!

Contact us at Volunteer@BillionGraves.com to learn more. We especially love helping groups to plan cemetery documentation projects!

Here’s an Irish proverb to you, from us: “May neighbors respect you, trouble neglect you, angels protect you, and Heaven accept you.”

Volunteer

If you would like to take gravestone photos, click HERE to get started. You are welcome to do this at your own convenience, no permission from us is needed. If you still have questions or concerns after you have clicked on the link to get started you can email us at Volunteer@BillionGraves.com.

Happy Cemetery Hopping!

Cathy Wallace