Victorian cemetery traditions were very intimate. Funerals were often held in the home and mourning periods lasted for decades.

Today, death is more removed from everyday life. Most people spend their final days in a hospital or nursing home. If someone does die at home, we pick up our phone and our credit card, and the deceased is whisked away. Funeral arrangements are handled by morticians and services are held at mortuaries.

An American surgeon, Sherwin B. Nuland, who taught bioethics at the Yale School of Medicine observed, “Modern dying takes place in the modern hospital, where it can be hidden, cleansed of its organic blight, and finally packaged for modern burial. We can now deny the power not only of death but of nature itself. We hide our face from its face, but still, we spread our fingers just a bit, because there is something in us that cannot resist a peek.”

Death was a common part of the Victorian world. There were epidemics and sickness. Families had more children and many of them died young. It wasn’t uncommon for families to lose as many as half of their children before they reached adulthood. Consequently, people went to a lot more funerals during the Victorian era than we do now.

England’s Queen Victoria is credited with giving the era many of its traditions. Her husband, Prince Albert, died suddenly within a month of contracting typhoid fever at the age of 42.

They had been married for 21 years and had 9 children together.

Queen Victoria was devastated. She wrote to her daughter soon afterward: “How I, who leant on him for all and everything—without whom I did nothing, moved not a finger, arranged not a print or photograph, didn’t put on a gown or bonnet if he didn’t approve it shall go on, to live, to move, to help myself in difficult moments?”

On the day of Albert’s funeral, every shop in town was closed and every blind was drawn. The streets were silent and nearly empty. All who went out were dressed in the deepest mourning clothes.

Victoria had the prince’s rooms maintained exactly as they had been when he was alive. Servants were ordered to bring hot water into his dressing room each day as they had formerly done for his morning shave.

She commissioned statues of Albert and displayed mementos of him in all the royal palaces. She went into seclusion at Windsor Castle and in Balmoral in Scotland, where she had formerly spent so many happy days with her husband.

Queen Victoria continued to mourn Prince Albert by wearing black for the remaining forty years of her life.

Following Victoria’s example, it became common for families to carry out extravagant rituals to honor their dead. These included wearing mourning clothes, hosting an expensive funeral, and erecting an ornate gravestone or mausoleum at the gravesite.

Today when we speak of “keeping up with the Joneses” it often refers to having a well-manicured lawn or owning a nice car. But the unspoken competition between prominent families in Victorian society was to have elaborate funerals and mourning rituals.

Is it possible that only four or five generations ago things were this different when someone died? You will better understand the world your ancestors lived in as you learn about Victorian cemetery traditions.

Victorian Cemetery Traditions #1: A Basket Case

During Victorian times, most people died at home in their own beds following an illness. Doctors visited to tend to their needs and later to determine if they had died.

If someone passed away when they were not at home, perhaps in an accident while traveling or at work, their body was transported home in a lidded wicker basket shaped like a coffin. These were called “removal baskets”.

Doctors or coroners who declared the person to be dead coined a new phrase by referring to the deceased as a “basket case”.

We still use the phrase “basket case” today to refer to a person or thing that is regarded as useless or unable to cope.

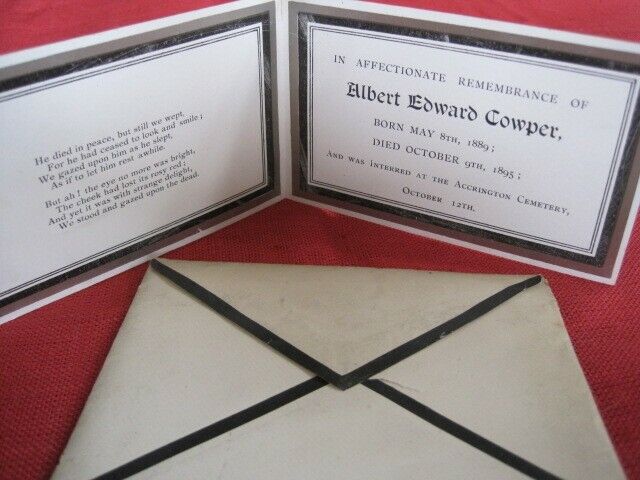

Victorian Cemetery Traditions #2: Black-bordered Funeral Invitations

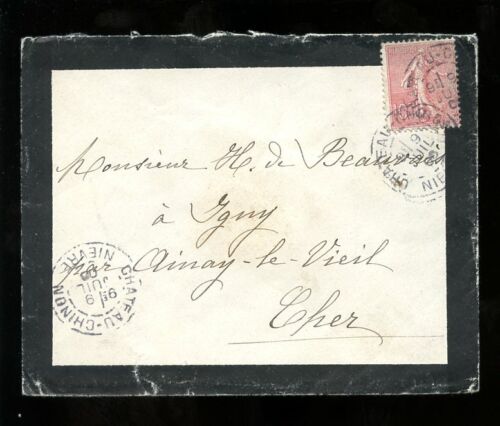

Victorian-era guests were invited to funerals by written invitation. The invitations had black borders and were usually delivered by a private messenger.

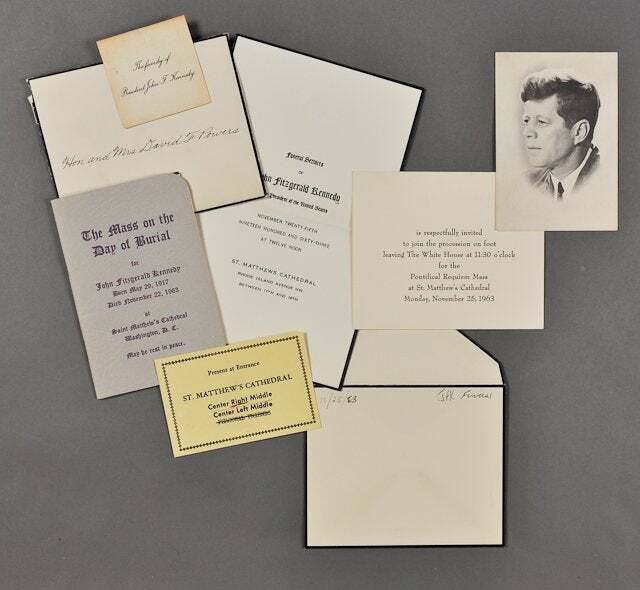

Black-bordered invitations are a Victorian cemetery tradition that continued to be used for more than a century.

It was considered improper to attend a funeral without an invitation. Once such an invitation was received, it would be considered improper not to attend the service.

Black-bordered invitations and envelopes were used for US President John F. Kennedy’s funeral.

The family of the deceased also used black-bordered personal stationery and envelopes during the mourning period.

Victorian Cemetery Traditions #3: Black-bordered Handkerchiefs

Victorians in mourning also carried handkerchiefs with black borders.

A wide border indicated a very recent death.

Victorian ladies carried handkerchiefs like this one made with a black handmade Chantilly lace border during mid-mourning periods.

The borders were narrowed as time passed and the expected mourning period came to an end.

Victorian Cemetery Traditions #4: Coffin Mirrors, Bells, and Tubes

The medical field was still developing during the Victorian era so doctors sometimes mistakenly pronounced people dead. The person may then revive after a few days, only to discover they were trapped in their coffin.

There are many stories of people being buried alive after falling into a vegetative state. The condition was dubbed “sleeping sickness”. Today we would say they were in a coma. Understandably, this caused widespread fear of premature burial so the Victorians put a few safeguards into place.

Some families buried a loved one with a rope in their hand, attached to a bell on the outside of the coffin. Then, if the person in the grave awoke, they could ring the bell to signal their need for help.

We still use the expression “saved by the bell” which orginiated with this practice.

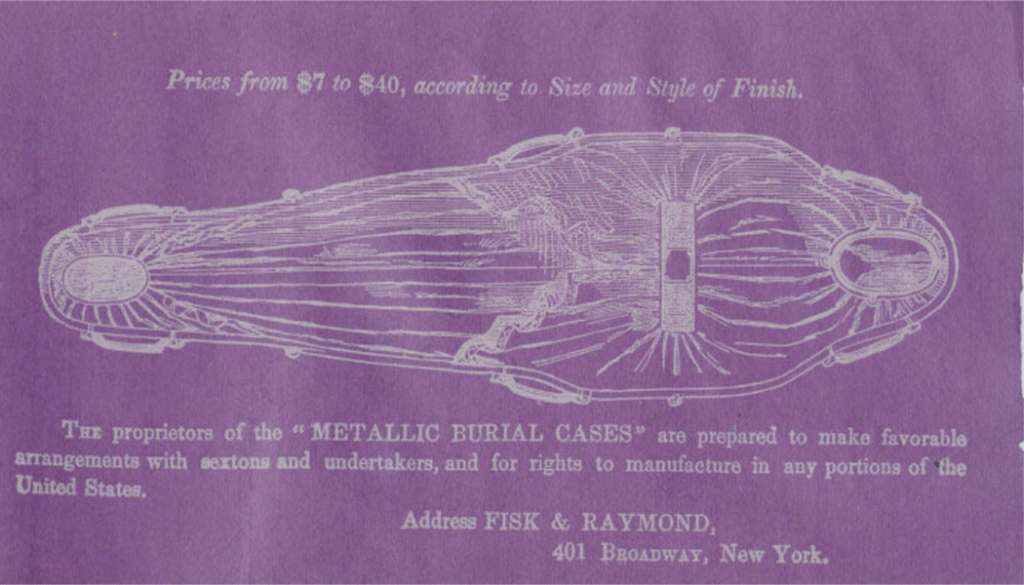

Some deceased were buried in coffins set up with glass windows and mirrors so that family members and gravediggers could peer into the coffin and look for movement.

Other coffins had breathing tubes installed.

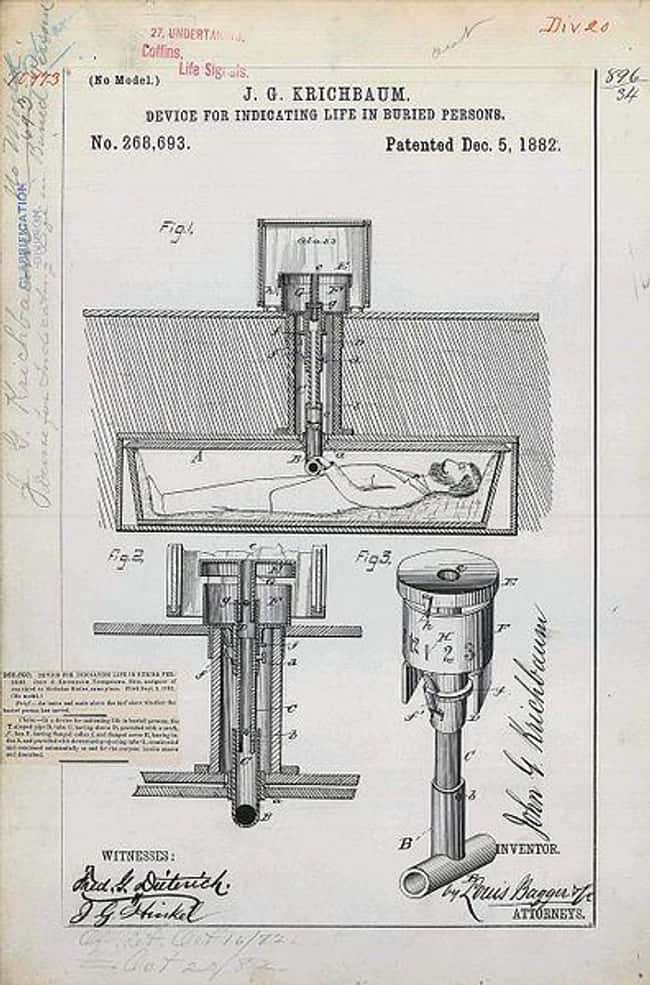

In 1882, inventor John G. Krichbaum of Youngstown, Ohio received a patent for a device that allowed interred people to signal from their coffin that they were still alive. Undertakers attached a handle to the supposedly deceased person’s hand. The handle was connected to a pointer that was aboveground, encased in a glass box.

Kirchbaum’s device also had tubes that allowed air to enter the coffin, keeping the interred person alive until help could arrive. It was recommended for “persons buried under doubt of being in a trance.”

Victorian Cemetery Traditions #5: Draped Hearse Horses

Hearse horses were draped with crocheted blankets. The blankets served two purposes.

First, they kept the flies off the horse. Second, they sent a message about who had died.

Black horses with black blankets were used for those who had died in old age. White horses with white blankets were used for children.

Likewise, a black hearse was for those of mature years and a white hearse was for little ones.

If the horses were white and the hearse was black, the deceased was a teenager or unmarried young man or woman.

Victorian Cemetery Traditions #6: Ostrich Feathers

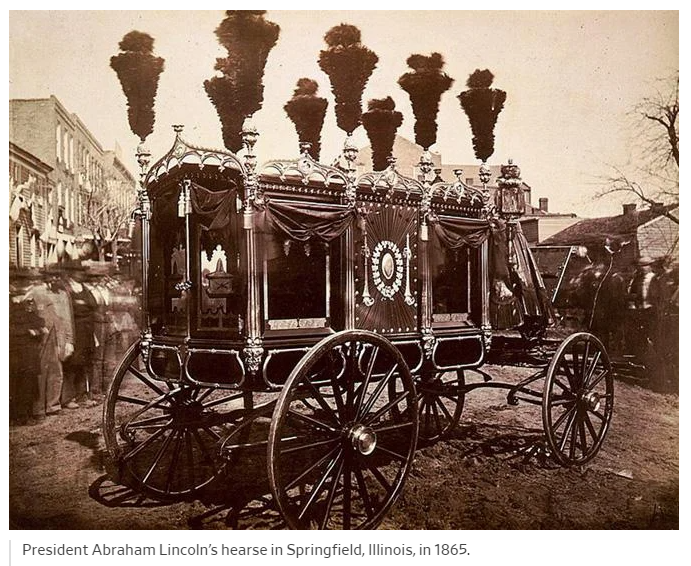

British royalty and nobility had a huge impact on Victorian cemetery traditions. In 1852, the Duke of Wellington’s hearse was pulled by twelve black horses, each with a dramatic plume of black ostrich feathers.

Subsequently, ostrich feathers were used to decorate horses, hearses, and hats at all the finest funerals. It was generally assumed that the more feathers, the better the fellow.

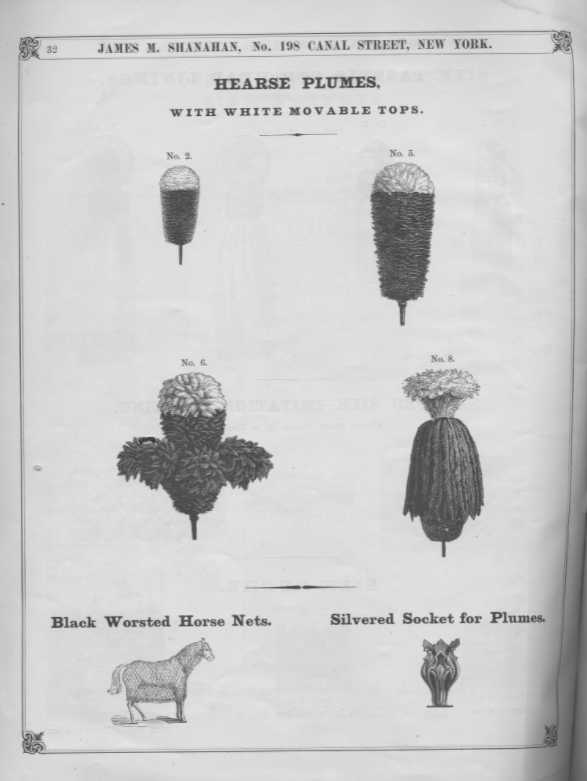

In 1869, the Illustrated Catalogue of Undertakers Hardware and Trimmings was published with a page of ostrich feather plumes for sale.

In the 1850s, ostrich feathers were rare and expensive. There were white feathers, black feathers, and gray feathers. Some were dyed pink, yellow, or purple. They were shipped to nations around the world from wild South African ostriches.

Some elaborate funerals had ostrich plumes decorating every corner, horse, and attendant. Wealthy guests wore them too. There were even entire canopies of ostrich feathers above the coffin during viewings.

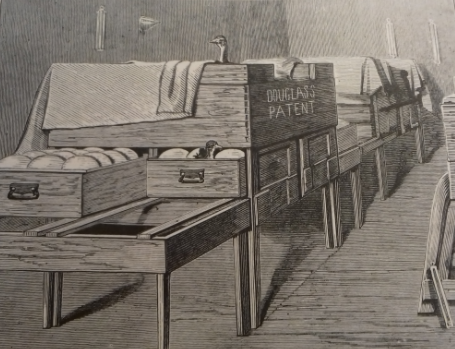

But by the late 1880s, farmers had started hatching ostrich eggs and domesticating ostriches which caused the feather market to become flooded. A patented ostrich egg incubator was invented.

Ostrich feathers suddenly went out of style (which is a good thing or you would probably be wearing one now) and funerals became featherless.

Victorian Cemetery Traditions #7: Professional Mourners

Another one of the Victorian cemetery traditions that demonstrated their “oh, look-at-me” attitude was the hiring of professional mourners.

Professional mourners were also known as “mutes”. Their job was to keep the tone of the day’s events sad and serious.

During the Victorian era, it was considered inappropriate to cry in public. Loud crying was especially discouraged so the mute’s silent demeanor helped set the tone. This also helped family members to keep up stiff appearances as custom demanded.

Mutes were expected to be silent and look despondent throughout the funeral proceedings. Their first task was to stand vigil day and night outside the door of the deceased. Then they trailed behind the coffin on the way to the cemetery.

Charles Dicken’s fictional character, Oliver Twist, is an example of a mute. He was hired by the undertaker Sowerberry to mourn at children’s burial services. Hiring a mute was expensive but it was also expected – even for modest funerals.

Dickens mocked the practice in one of his novels by saying, “Two mutes were at the house-door, looking as mournful as could reasonably be expected of men with such a thriving job in hand.”

Victorian Cemetery Traditions #8: Mourning Jewelry

Some families created mementos using a loved one’s hair. They artfully arranged the hair in shadow boxes, wreaths, corsages, and especially in jewelry.

The hair was woven or braided and fashioned into bracelets and necklaces.

It was considered unseemly for a woman to wear jewelry during deep mourning but they often wore a jewelry memento afterward.

Family members and close friends sometimes wore mourning jewelry for decades to come.

Mourning jewelry often had a black gemstone called jet in it as well. Jet is also known as ignite and is a type of fossilized wood that became coal.

Human hair was also encased in brooches to be worn at the neck of high-collared woman’s dress.

Other types of jewelry included ivory rings and pendants with mourning symbols on them such as willow trees, urns, or clasped hands. Some had the initials of the deceased on them.

Gold lockets were worn by both men and women and often included a portrait of the deceased.

Queen Victoria wore a locket that contained a picture of Prince Albert and a lock of his hair.

She also had a miniature crown custom-made to wear over her widow’s cap to the funeral. It contained 1,162 brilliant and 138 rose-cut diamonds and weighed 132 carats.

Victorian Cemetery Traditions #9: Black Ribbons for All

If several members of the same family died, everyone and everything that entered the house was expected to wear a black ribbon to prevent the deaths from spreading even further.

A complete wardrobe of black was appropriate for close family members. Visitors could get by with tying a black ribbon around their arm.

Crepe, a lightweight silk fabric that was processed to remove any sheen, was wrapped around the doorknob of the bedroom where someone died. It was used to trim dresses, cloaks, and bonnets as well as to hang on over mirrors and pictures during the grieving period.

This black-ribbon or black-tie practice even extended to dogs . . .

. . . and to chickens.

Victorian Cemetery Traditions #10: Elaborate Mausoleums

Mausoleums are buildings at a cemetery meant to allow family members to pay their respects in a quiet, peaceful setting. (Click HERE to read about some amazing mausoleums.)

Queen Victoria set the standard for mausoleums. She had the Royal Mausoleum built for Prince Albert and herself at Frogmore, England, adjacent to the Royal Cemetery where other British royals are buried.

The interior of the royal mausoleum was even more elaborate than the exterior.

Many families around the world followed Victoria’s example and saved for years to pay for an elaborate mausoleum. Children who died young may have had more spent on them in death than was spent on them during their lifetime.

The Victorians had plenty of chances to face death. Mortality rates for children were high and those who did survive childhood didn’t usually live past age 50.

Funerals were so important that middle and lower-class families sometimes went without the necessities of life, such as food, clothing, and shelter, rather than dip into their funerary savings fund.

Ironically, by refusing to use their funeral reserves to ensure the survival of their children, families were almost ensuring that they would need to use those reserves for their children’s funerals.

As Victorian mourning etiquette became more extreme, it caused great anxiety for the families of the deceased. A card with a black border too narrow, a colored dress worn too soon, a stroll in the park made too early — all could be interpreted as disrespect for the dead.

So eventually, many Victorian cemetery traditions were discontinued or simplified. But there are some that still impact the way we behave today.

Volunteering to Take Gravestone Photos

The BillionGraves app helps preserve family memories. We need your help to take photos of gravestones with your smartphone.

If you would like to volunteer to take gravestone photos, click HERE to get started.

Planning a group event? Contact us at Volunteer@BillionGraves.com for more resources. We’ll help you find a cemetery that still needs to have photos taken.

You are welcome to take gravestone photos at your own convenience, no permission from us is needed. If you still have questions after you have clicked on the link to get started, you can email us at Volunteer@BillionGraves.com. We’ll be happy to help you!

Happy Cemetery Hopping!

Cathy Wallace